Pro-Trump Georgia election board weighs new rules as critics warn of chaos

LAGRANGE, Ga. — The Georgia State Election Board is expected to vote on a measure to force counties to hand-count all ballots this year, a requirement that could delay reporting of results by weeks if not months and that critics say is designed to inject chaos and uncertainty into the presidential contest in a vitally important swing state.

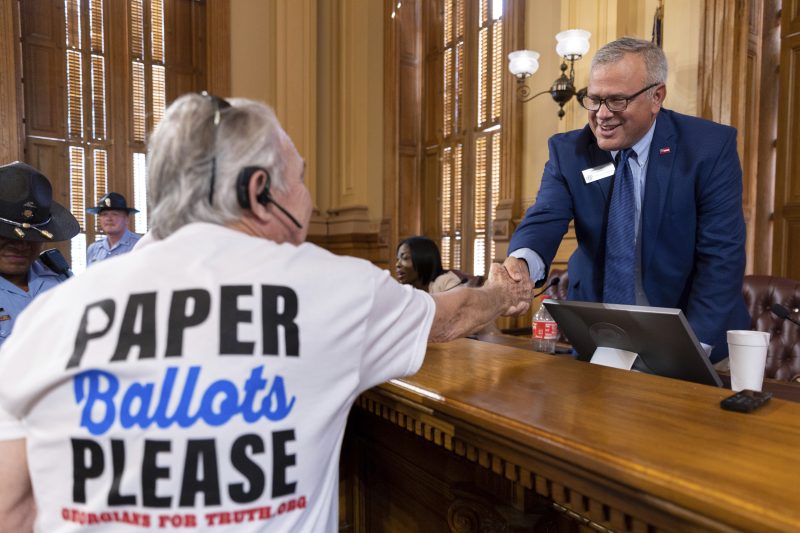

The board will take up the proposal, which would require the hand count in addition to the customary machine count, Friday morning at the state Capitol in Atlanta. If passed, the measure would mark the latest rule the panel has adopted in recent weeks in an effort, proponents say, to make state elections more secure and transparent.

The flurry of rulemaking is the work of a new right-wing majority that took control of the board in May with an avowed mission of preventing fraud and other irregularities from tainting the presidential result this year. All three are supporters of former president Donald Trump, and the rules they are pushing have been promoted by the state’s leading proponents of the false claim that President Joe Biden stole the Georgia election in 2020.

State and local election officials warn the rules would upend the presidential contest in Georgia — an electoral battleground that Biden won by fewer than 12,000 votes four years ago out of some 5 million cast.

“We’re passing these things without really listening to people,” said John Fervier, the chairman of the state board, who opposes the rulemaking spree. “This board should take a more deliberative approach. We should involve all stakeholders including the secretary of state, attorney general, local election officials, citizens and the legislature. We’re passing these rules without taking the time to properly consider them.”

With just over six weeks to go until election day, the rules are also going into effect far too close to the vote, Fervier and others said. Counties have not had time to train their workers on new procedures, nor hire the staff that would be needed to tackle the enormous task of a hand count.

Democrats have already sued over a rule passed earlier this year that could allow counties to delay certification, with a hearing scheduled Oct. 1. More litigation is expected if the board adopts additional rules Friday.

Research and practice have shown again and again that hand-counting of ballots is less accurate than machine tallies — and that it can take days, weeks or months, depending on the size of the jurisdiction. A hand-counted audit of 2.1 million ballots in Maricopa County, Ariz., after the 2020 election took more than two months.

Most jurisdictions in the United States already audit election results by hand-counting a sample of ballots and comparing the results to machine tallies. They do so after unofficial results have been reported, encouraging confidence in the result without gumming up counting on election night.

An early version of the hand-counting proposal, which was proposed by one of the majority board members, Janelle King, would have required the count to take place on election night in each precinct. The board agreed to alter that proposal; the version to be taken up Friday would allow counties to begin the hand-count in their central offices as late as the next day. The rule requires three poll workers to count each precinct’s tallies independently. If their totals don’t match, they must report the discrepancy to the county election board. The hand count would be required to be completed within the week.

Bill Stump, a local banker and chairman of the Troup County Board of Elections and Registration, said among his concerns is the fact that the county parties are not always able to deploy election observers at every single precinct.

“If we’re going to hand-count ballots I would much rather do it in a controlled environment,” Stump told a luncheon meeting of the Troup County GOP in LaGrange this week, about an hour southwest of Atlanta.

King was the featured guest at the luncheon. She declined to discuss the rules that will come up on Friday “because I am still evaluating them.” King plans to appear at a news conference ahead of the board meeting with the other pro-Trump members.

Earlier this year, the board passed a rule that critics say could empower county boards to delay certification of results. The rule allows the boards to demand “reasonable inquiries” if they have questions about the outcome of an election. The rule does not specify what a reasonable inquiry is, and it places no limits on the time frame of such a probe or what documents a board can demand.

Georgia law requires county boards to certify their results by the Monday following an election, but critics of the new rule say it could lead boards to misinterpret their power and refuse to certify, thereby slowing the process of state-level certification. In a presidential election,the calendar for determining which presidential electors will convene and send their votes to Washington is fixed and inflexible, with disruptions having the potential to derail the process. This year, electors are due to convene in every state on Dec. 17, a precursor to the counting of electoral votes in Washington on Jan. 6, 2025.

Some critics say that because the hand-counting requirement would almost certainly inject error into the tabulation process, it could give county boards the evidence they need to investigate results and delay certification. Some questioned whether the two rules together amount to intentional sabotage of state elections.

“Requiring poll workers to hand count ballots after the close of polls will do nothing more than provide exhausted patriots with an opportunity to undermine public confidence through an honest mistake,” said Joseph Kirk, elections chief in Bartow County, northwest of Atlanta.

Democrats have filed a lawsuit seeking to block the certification rule, and are almost certain to sue if the hand-counting rule passes Friday.

The State Election Board carries a wide range of responsibilities, including investigating the administration of elections and recommending sanctions or even prosecution for mismanagement or fraud. It also makes recommendations for new laws and writes rules to promote uniformity and integrity in state elections.

It is a bipartisan board, with its five members appointed by the governor, the state House, the state Senate and each of the two major parties. Its role has typically been far less prominent than that of the secretary of state or others involved in administering Georgia’s vote.

The new majority’s clear partisan tilt has unsettled democracy advocates, county election administrators and the office of Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R), which sent a blistering letter to the panel this week denouncing the rules to be considered Friday, including one that would require changes to absentee and provisional ballots.

“To underscore the absurdity of the timing of the Board’s actions,” wrote Raffensperger’sgeneral counsel, Charlene McGowan, “[the ballots] have already been printed, and counties will have already begun mailing absentee ballots to voters before any rule change would take effect.”

She added: “It is simply impossible to implement this change for 2024.”

County election administrators have sent similar letters of concern, some imploring the board to at least engage with local officials to understand how disruptive their proposals could be. Several told The Washington Post they got no response from the board majority.

One local election board chairman from Camden County, along the Atlantic coast just north of Jacksonville, Fla., sent a letter to the state board with a long list of questions on how to implement the new rules. “We hereby request guidance for the implementation of the revisions,” Kyle Rapp wrote to close his letter, which he sent Aug. 22.

The pro-Trump board members are King, Janice Johnston and Rick Jeffares. Johnston is a retired obstetrician and GOP appointee who has served on the board since 2022. King, a former deputy state director of the state GOP, and Jeffares, a former state senator, were appointed by legislative Republicans this year. Fervier, the chairman, was appointed by Gov. Brian Kemp (R). The fifth member, Sara Tindall Ghazal, was appointed by state Democrats.

Trump called the three majority members out by name at an Atlanta rally over the summer and referred to them as “pit bulls fighting for honesty, transparency and victory.” Johnston was in the second row at the rally and stood to wave amid the accolades.

Neither Johnston nor Jeffares responded to requests for comment. The Trump campaign also did not respond to an inquiry.

Republicans and Democrats alike criticized Johnston for making an appearance at a partisan event during a fraught moment of the election cycle. The board’s work is supposed to be done outside the fray of politics, and Trump’s words suggested that if he loses the state, he would again mount a pressure campaign on the officials responsible for fairly and impartially overseeing elections, just as he did during his failed attempt to overturn his loss in 2020.

Trump has repeatedly declined to say he will accept the results of the 2024 election and has complained of Democratic “interference,” saying he believes the only way he can lose is if the other side cheats.

Josh Dawsey contributed to this report.